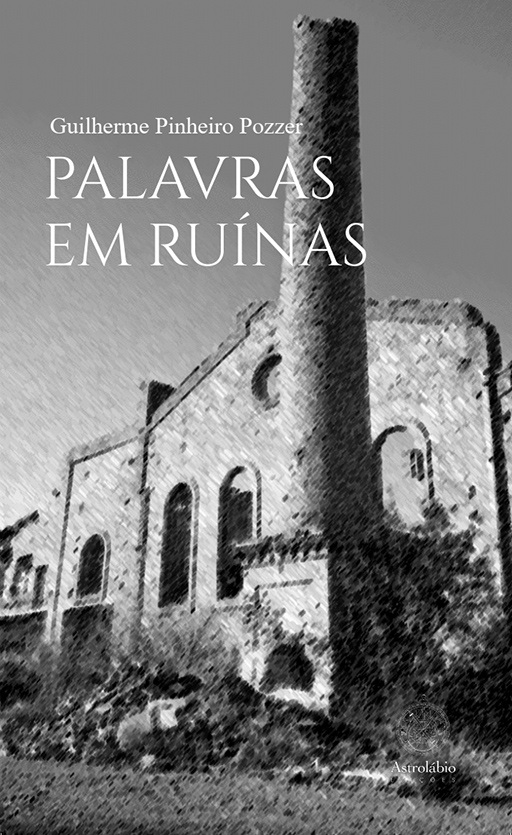

![]() 'Palavras em Ruínas (Words in Ruins)', by Guilherme Pinheiro Pozzer.

'Palavras em Ruínas (Words in Ruins)', by Guilherme Pinheiro Pozzer.

130 pp. Astrolábio Edições (in Portuguese), 2022. €12.00 (PB), €5.00 (Ebook). ISBN-9789893743980

Ruins are the realisations of another era. We can talk about a classical temple sinking into the desert sands, a pyramid hidden in the heart of the Amazon rainforest, or an ocean liner sunk at the bottom of the ocean. We can talk about the arch of the door bombed yesterday, at the end of the day, in a scene of horror that has yet to be washed away.

All ruins take us backwards or forwards to the mystery of entropy. They are material testimonies to the false eternities of history, warnings of our own mortality. They are like the breath of Tiresias on our faces. In this way, like the Nietzschean abyss, ruins, when contemplated, also contemplate us back. The ruins, however, are not empty: underneath the silence, there is something to listen to.

The way we behold the ruins is also different for each of us. One of today's most fascinating ruinologists, Tim Edensor [1], tells us in one of his first lines about the attraction that the Scottish baronial style mansion at the top of the hill exerted on him as a child. How this feeling awoke in him, between awe and curiosity, the spirit of exploration. The same spirit that would lead him, years later, to embrace the study of English industrial ruins, in what he called the golden age of industrial ruination.

It is these industrial ruins, fragments of a past of production, appropriation and accumulation, that serve as the starting point for the immersion that Guilherme Pozzer experienced when he studied the foundation, development and decay of the industrial cotton factory of Riba de Ave, in Vila Nova de Famalicão, in the north of Portugal [2]. It was precisely from this work, which would culminate in his PhD dissertation, that I first came into contact with Pozzer's research.

The first time I went to Riba de Ave was in February 2017, in the rain... the eternal rains of the Ave, the lethal rains that Pozzer reminds us of so often... (those rains of 1966, that May, the cruellest month). On that first visit, I was looking for a ruin that I wasn't sure even existed. Nobody knew. I was looking for the first factory in the region, also a textile factory, but in this case, a woollen mill. There were documentary records, there was even a literary passage, alluding to the factory's waterwheel, spinning somewhere in the 1880s, but nobody knew if there were any traces of the small mill left.

I went down to the right bank of the river, gazing at the large shadow of the ruins of the big factory, like the shadow of Hercules in hell. Walking carefully over the slippery rubbish on the bank, I saw, on my side, a fire coming out of an old tin can and, further back, a tent, almost a ruin itself. A man came out of the tent, stirred the fire and looked at me. He introduced himself and asked for something, a cigarette or some change. He told me that it was he and some other men, mounted on a small, unstable raft in the river below the dyeing plant, who had dismantled the last turbine in the factory. Was this the original but reused wheel from the factory I was looking for? Most likely yes, but the wheel, and the luck of it, no longer existed. But the hands that had dismantled it some 50 years ago were there. The same hands that had also switched on the radio on the roof of the small, isolated building, just opposite, where the second chimney of the large factory stands. The second chimney dates from 1911, but the radio I'm talking about was switched on very early, on the morning of 25 April 1974. The day of the Revolution [3], which that man, plus his maintenance colleagues, that man in front of me, without a house and without a factory, celebrated in real time, on the roof, what he understood to be his (and everyone's) liberation. He had quit his job shortly afterwards and started his own business. He had lost himself, lost everything and was now returning, not to the factory he had left, but to its ruins, or rather to the edge of the ruins.

I was struck by this human story. A story that no longer exists. Perhaps it ceased to exist even in that winter of 2017. What existed, and still exists, is the small factory I was looking for. It was simply the small building where the radio on the roof had once given hope to the maintenance men, even though it had been remodelled and swallowed up by the big factory. Of all this, what I kept, in my academic zeal, was the history of the factory. Its foundation and decline. The man, and others I met later, were not part of the academic articles. I referred to them sometimes, I haven't forgotten them, but they haven't been part of the narrative of work and space for a hundred and something years. For me, methodology was still a watertight pit, dazzled by archaeological discoveries that, by convention, don't seem to incorporate the living.

I later realised that methodology is something we make. The choice to bring life to the ruins (and life is also the memory of the dead) is entirely ours, the researchers. For my work in Riba de Ave, this realisation came late (I only read Mary C. Beaudry's Documentary Archaeology, but then also Laurie A. Wilkie, a few years later [4]). For Guilherme Pozzer, this knowledge came early and was cultivated.

Palavras em Ruínas (Words in Ruins), it's a compilation of 33 literary fragments, short glimpses, between poetry and prose, the news of memory, of its labour justice , is precisely the exercise of this homage to labour, to workers. To their memory, to the memory of those who came before them and those who come after them. Each of the texts takes us, sometimes with the peremptory rawness of reality, at other times with the metaphor of words, into the world of the wronged women, men and children who, before the ruin, made the material that came to be, just as in the bronze man's dream and Pozzer's words, the factory that was as if it were, but also no longer was.

-

[1] The gothic ruin which is mentioned in this book review was an incomplete mansion. Building work started in the early 1900s but this ceased about 1913 and the unfinished building was left to decay. The ruin was quite close to Tim Edensor's grandparents' cottage in the West of Scotland and it fascinated him as a child.

See the book review in GLIAS Newsletter 339.

[2] Portuguese and Spanish speaking industrial historians and archaeologists are currently taking an interest in the textile mills in the north of Portugal. They are not considering just the physical remains but also the aftermath of industrialization, the people there now bereft of industry are not doing at all well. So this work is not only about the hardware but also about what has happened to the people. There is a sociological element involved.

[3] This almost bloodless Portuguese revolution in 1974 brought about the end of a fascist dictatorship which had existed since 1933.

[4] Wilkie, Laurie, 2006. Documentary Archaeology. In The Cambridge Companion to Historical. Archaeology, ed. by D. Hicks and M. C. Beaudry. Laurie Wilkie is a professor in the Anthropology department at the University of California, Berkeley, USA

Mário Bruno Pastor, CITAR - Catholic University of Portugal. mbpastor@ucp.pt

Guilherme Pozzer intends to publish an English edition of the book.

Readers preferring to have this review in Portuguese may contact the book's reviewer.